Book II

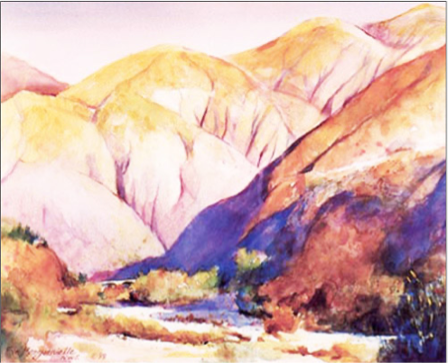

San Gabriel Mountains,1998, 22×20 WC,

by Eva Margueriette NWS, Kommerstad Collection

1. Rites of Passage

The sins of the fathers are to be laid upon the children–William Shakespeare

THE DEVIL SANTA ANA blew in last night from the upper Mojave Dessert fanning wildfires, suicides, and ripping branches off our century-old, blue-gum eucalyptus standing sentry too close to the house. Oblivious to my gratitude the trees hadn’t crashed through the roof, Terry and Melissa, his younger sister, ate ketchup-smeared eggs on English muffins, grabbed their lunch boxes, and ran out the door headed for Royal Oaks Elementary School.

Preparing for my upcoming one-woman exhibition, I’d spent the day working on a large painting, A Tribute to Pablo Casals. When the phone rang in my kitchen studio, I dropped my brush on the palette, removed my powerful hearing aid from my better ear and pressed it against the receiver on my amplifier phone. “It’s Mrs. Strong.” I recognized my son’s new fourth-grade teacher’s name. “Did you know Terry’s been absent for two days?”

My hand hit my heart. “That’s impossible! I saw him leave. He took his lunch box.”

“There’s something else,” she said. “We just caught him smoking in the bushes with a sixth grader named Alex.”

“Alex?” More than eucalyptus trees falling on the house, I feared our next-door neighbor’s influence on Terry since that day the boys jumped off our roof last summer.

Afraid to ask, I never learned how they spent those two days. Looking back, I suspect I avoided asking because I didn’t want to know.

A newspaper printer, my husband worked the swing-shift from three to eleven PM. Before he left that afternoon, I told him our son ditched school, and we must attend a parent-teacher conference the next morning. I retrieved Terry from the principal’s office. Tears flowing down his cheeks, he promised he’d never lie to us again. He and his sister ate hot dogs and tater tots. We went to bed early, but I didn’t sleep. Again, all night, the wind howled like a hurricane on dry land, windows rattled, branches ripped from the eucalyptus trees slapped the roof.

The bedroom curtains drawn against the morning light; Stuart’s thin five-foot-nine frame, clad in blue checkered boxers sprawled across our queen size bed. Eyes clouded, his body reeked of stale beer, I touched his shoulder and whispered, “It’s time to go to the conference.”

He pushed my hand away. “I’m not going!”

“I promised the teacher.”

“Nope! I’m too tired,” he said, pulling the sheet over his head.

“Dammit, Stuart, I’m tired too!” I screamed and slammed the bedroom door.

In the bathroom I applied mascara to hide my fatigue, wriggled into flesh-toned pantyhose and a too-tight pleated-skirt bunched at the waist. Walking to my children’s school, inhaling air washed clean by wind, no rain, gusty winds whipping at my feet, I imagined my life blowing away like the fuzzy tufts on the dandelions growing in the sidewalk cracks.

On my left, the San Gabriel Mountains, rising ten thousand feet above the valley as they had for eons, glowed pink, translucent in the morning light. At eight, soon after moving from Bisbee, I stood neck crooked, gazing at Mount Wilson. “You can’t get lost in this valley,” my Uncle Green said. “Just look toward the mountains. They’re always true north.” Since that day, I believed in guidance that helped me to navigate life without a compass.

At the school entrance, orange remnants clung to the limbs of the liquid amber sapling ravaged by last night’s storm. Beyond the tender tree, children dashed across the sunburnt grass, laughing. Climbing the steep sidewalk led to Terry’s classroom wedged in the foothill slope. Newsprint penned in fourth-grade cursive lined the corkboard walls behind Mrs. Strong, well-coiffed and a bit older than me sitting at her desk against a wall of windows framing the mountains, close enough to touch.

Making excuses for my husband’s absence, I squeezed into a child-sized desk opposite the teacher, waiting to be reprimanded for my failure as a parent.

“Ditching school and smoking may be a sign of a deeper problem,” she said. “A cry for help. Is Terry upset about anything? Any problems at home?”

Considering Stuart’s nightly drunkenness my problem, I said, “No, everything’s fine.”

In that case, she said, perhaps a doctor could prescribe Ritalin, a drug to help him control his impulsive behavior, to help him focus.

Focus? Granted, jumping off the roof with Alex last summer seemed a bit impulsive, but Terry knew how to focus. He played the accordion, pitched in Little League, and since reading The Secrets of Magic, he spent hours practicing sleight-of-hand, card, and coin tricks.

And I couldn’t tell her why drugs scared me, doctor prescribed or not. Addicted to nicotine like my mother, sister and husband, I started smoking at eighteen and taken amphetamine-laced diet pills prescribed by our family doctor, on and off since seventh grade. My mother, a registered nurse, washed her prescription down with Coke and Jack Daniels.

God knows, I’d tried to stop drugging myself and that I worried though Stuart could be, he might not be Terry’s biological father, but an art school friend’s brother, a one-night-stand drug addict just released from prison.

“My son’s only nine,” I said. “I don’t want him taking drugs!”

Her voice softened. “I’m only asking you to consider it.”

The kindness in Mrs. Strong’s voice brought tears to my eyes and muddied my mascara. “Thank you,” I said, wrenching my body from the desk chair.” I’ll think about what you said.”

Walking in the shadow of the mountain bleached gray in midday sun, I arrived home, cleared my palette and paint rags off the kitchen table, peeled potatoes, and shoved a chicken in the oven to roast for an hour. Since we married, Stuart expected me to cook like his Pennsylvania Dutch mother, a good cook, also named Eva.

“Beans are a side dish!” he scowled the the first time I served pinto beans and cornbread as a main course, my Southern family’s favorite dinner. We both craved our childhood comfort foods, but I gave up cooking my black-eyed peas, red beans, lima beans and ham hocks, and warmed up canned peas and creamed corn and cooked potatoes: mashed, baked, or hash browned. The daily menu included roast beef, chicken, or meatloaf—but always potatoes.

Stuart dragged himself out of bed, shaved and settled at the head of the kitchen table. “What did the teacher say?” he asked, scooping mashed potatoes on his fork.

“She said it’s serious.” I didn’t mention she suggested a doctor who’d give him drugs.

“Don’t worry. a little father-son chat ought’a straighten him out,” he said, pulling a cigarette from his shirt pocket.

After school, father and son faced each other across the kitchen table. The sun beamed in the window. Terry’s freckled face bathed in Rembrandt lighting, he resembled the Dutch master’s brooding portrait of his young son, Titus, the artist’s only child who’d survived infancy.

“How’d it go?” I asked.

Looking pleased with himself, he said he’d grounded Terry from that troublemaker, Alex. “Everything under control,” he said grinning. “You know, boys will be boys!”

Perhaps, puberty blew in like a windstorm when least expected. My sweet boy seemed too young to relinquish childhood, but adolescence loomed on the horizon. I considered Terry smoking at school, a wakeup call. Did Stuart consider the crisis a mere incident?

I cornered him in the hallway and told him we both must stop smoking because our children needed better role models. “If we’re smoking, we can’t forbid them to smoke!”

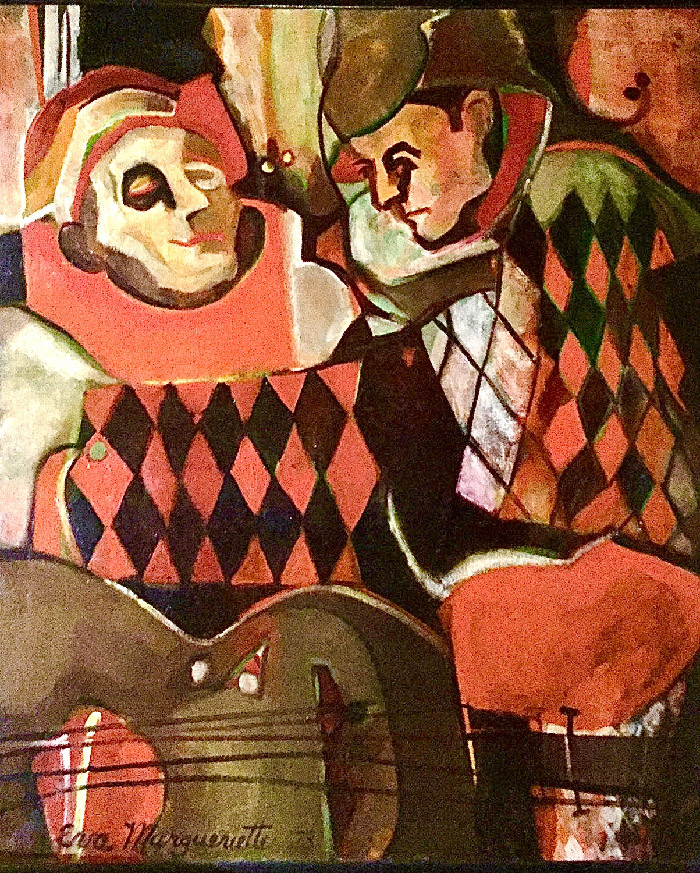

“I’m not going to quit. Stop bugging me about it!” he said storming out. Leaning against the car in the driveway, he cupped his hands to protect the flame from the wind and lit a Camel. In profile, he looked like the Trickster, the sinister clown I’d painted in The Harlequins.

What did he mean, “Boys will be boys?” Like his father, Stuart started smoking at thirteen. Did my husband consider our nine-year-old boy smoking and ditching school some sick sort of masculine bonding? Mrs. Strong suggested playing hooky and smoking signaled a deeper problem, confirming my fear that the sins of the fathers had already passed to the next generation, our son. I wanted to believe Stuart had everything under control and the crisis a normal rite of passage, like he said, “You know, boys will be boys.”

I stood in the doorway inhaling the minty aroma of the thirteen eucalyptus trees towering over the backyard and our house. Their long silvery leaves hung limp, pointed toward the earth, denying the mayhem of last night’s storm.

![]()

The Harlequins, 1973, 30×36 inches, Oil on canvas

by Eva Margueriette, Artist’s Collection

2. The Harlequins

In mythology, folklore, and religion, the trickster was a creative magician who exhibited high intelligence, played tricks, disobeyed rules, and defied conventional behavior.

I QUIT PAINTING SOON after graduating from CalArts and for the next five years channeled my creativity into mixing paint at my children’s nursery school, and learning to sew potholders, bedroom curtains from bedsheets and Hawaiian muumuus because nothing else fit.

One night, a neighbor invited me to attend her macrame class at Covina Adult Education. During the break, I discovered Mr. Claude Ellington, a renowned artist teaching figure drawing who encouraged me to join his class, and the following week I arrived toting my large drawing board, paper and box of vine charcoal. When the model assumed his first pose stark naked, I complained to my new teacher that in art school, male models always wore jockstraps. He assured me in a fatherly voice that things had changed in five years.

Eager to reclaim my creative spirit, I enrolled in all his figure, portrait painting and still life classes. After studying with him for three years, he suggested I launch a one-man-show of my recent work and months before Terry ditched school; I secured gallery space in the Duarte Public Library for an exhibition.

Mrs. Strong didn’t call us again and assuming the crisis resolved, I focused on designing and mailing an invitation to everyone I knew, named my paintings and made title cards, planned a post exhibit champagne party at our house, and printed a price sheet as if I might sell something.

I framed the best paintings, including my first cubist piece inspired by Cezanne’s Mardi Gras, Pierrot, and Harlequin. Terry, eight and Melissa, five posed for The Harlequins, exploring Carl Jung’s archetypes in our collective unconscious. In the garage, my daughter stood posing as the devilish dancing clown. Her brother sat beside her pretending to strum the guitar. Intent on recording their innocence in charcoal marks, I forgot to give them their every twenty minute, five-minute model break.

“How long do we have to sit still?” Terry asked.

“Take five!” I said. Unable to answer the phone, drink coffee or evaluate my work during model breaks without a cigarette in hand, I lit a Kool and flicked the ashes into the metal ashtray inherited from my mother. I hated her smoking and vowed never to be like her. Puffing on a cigarette, I wondered what my children thought of me.

Imitating Cézanne, I clothed my harlequins in cadmium red and black rhombus shapes, painted the trickster’s profile in dark wicked lines and bells on his hat that jingled when he twirled. “The clowns don’t look like us,” Melissa said.

Terry squinted at the canvas. “What’re you making, Mom?”

“Music, magic, mayhem!” I said, imagining a medieval passion play. Drama. Pandemonium. The trickster taunting the lute-playing clown, my son.

On opening night, December 3, 1974, with my long dark hair curled, I stood in the library gallery surrounded by my ink-wash drawings of live models and cubist oils painted in the kitchen. Our friend. neighbor, and professional photographer, Jim Jarboe arrived first, because he’d volunteered to shoot black-and-white photos of the guests at the opening reception.

Within minutes, Cathy and Ken Peters, a journalist at Stuart’s newspaper, bought Cleo, an ink wash drawing of my favorite model, for $45. The librarian congratulated me on my first sale. “You can stick these on the sold paintings,” she said, handing me a box of gold stars from her desk.

Soon, a nursery school mom chose The Bagpiper, a 30 x 40 oil, for $300. A neighbor bought Meditation, a Self-Portrait, painted in thin oil washes and charcoal line. Stuart promised to buy me a dishwasher in exchange for what Mr. Ellington called my masterpiece, A Tribute to Pablo Casals.

Two hours later, more than half the paintings sold; everyone came to our house to celebrate my success, including my mother, who expressed her anger because I neglected to introduce her as the guest of honor at the library reception.

“I’m proud of you, Eva!” Mr. Ellington said, sipping champagne with his wife. That night, envisioning angels floating above my bed, I fell asleep happier than at any time in my thirty years of living.

The next day, sitting at the kitchen table, I handed Stuart my gold-starred price sheet. “I’m so happy about the success of my show.”

“Success?” he said, scanning the numbers. “How much did you make?”

“Look!” I pointed to the seventeen shiny stars stuck on the sheet. “$1600!”

“I mean profit.” He meant what remained after subtracting the cost of art supplies, stamps, invitations, frames, and champagne.

“I bought the champagne on sale,” I said.

He waved the price sheet in my face. “You didn’t charge enough. The paintings should cost more than the frames.”

Did the three joyful years I spent drawing live models and painting all night in the kitchen amount to nothing? What about the art lovers who attended the exhibit, and those who bought my paintings? Neither of us appreciated the gift of people in our lives nor the fact that artists seldom made a profit in the beginning.

Preparing for the exhibit, I believed I could be a real artist after all, but my husband was right. I didn’t know what to charge, and afraid of asking too much, I didn’t ask enough. I knew so little about business and nothing of my worth.

“So, my show wasn’t a success?”

“Success,” he said. “Is a matter of profit and loss.”

The following evening, Jim Jarboe spread a stack of 8-by-10, black-and-white photos on our coffee table. A creative photographer, he’d captured Terry holding a pen in his dimpled hand signing the guest book in fourth-grade cursive, Melissa in her nightgown sprawled in the recliner at our home reception, and my you’ve-got-to-be-kidding expression when the Peters bought Cleo, my first sale.

(EXHIBIT PHOTO Here -width of type)

Eva Margueriette, Exhibit photo by Jim Jarboe, 1974

Posed in front of The Harlequins, my hair and black-clad torso merge into the painting as I greet a fellow Women Painters West member, Mr. Ellington in his dressy leather jacket, stands behind me, his back to the camera. The woman in the bottom of the photo exhibits the same-shaped face, hair, partly closed eyes, nose, and peaceful smile as the seated harlequin modeled by Terry.

I’m clutching my tiny box of gold stars, a teacher’s reward for stellar performance. In profile but looking in the opposite directions, my facial features match the sinister, dancing clown in The Harlequins, the one I accused Stuart of emulating that day he refused to stop smoking.

Every portrait is to some degree a self-portrait of the artist. Studying the apparition captured on film in that split-second click, I realize I painted the Trickster’s face a mirror image of my own.

There is nothing to fear, the angel says.

Every word spoken and unspoken, every action taken and not taken occurred exactly as it should be and in perfect order. Love is all there is. It’s all so beautiful, complete with the music.

And this music will play until this story is told.