PROLOGUE

Pee Wee, ink wash drawing by Eva Margueriette

A Young Artist

The only gift is a portion of thyself. The poet brings his poem,…

The painter brings her picture — Ralph Waldo Emerson

BANGING THE BASS NOTE keys, I pretend to play the piano in the deserted country club social hall, making sound vibrate in my four-year-old bones. I don’t know I’m almost deaf. No one knows yet that a fevered bout with Meningitis two years earlier burned out most of the nerves in my inner ears.

Now, almost eighty years later, I picture the aftermath of a forest fire that destroyed every tree, except one. That lone tree represents my twenty percent residual hearing in low-toned frequencies.

In the year of my birth, 1944, the world was at war to end all wars. My father, who served as a cook in the army, is now a chef cooking in a private club near Bisbee, Arizona, a copper-mining town on the Mexican border. My parents, Jeanne, my baby sister, Mammaw, my mother’s mother, and I sleep on cots in the storeroom off the kitchen.

One night, my father storms out the door, leaving my mother curled on her cot, crying. I rub my eyes and go back to sleep, telling myself it’s just a bad dream.

“Mommy,” I ask, days later. “When’s Daddy coming home?”

“I don’t know. He went out to buy a pack of cigarettes but never came back.”

Mammaw says we’re moving to a real house.

I miss playing piano in the sunlit social hall, but I love sleeping with my mother in a big bed beside the window in our little rented house on Douglas Road across from Evergreen Cemetery. Sitting on the slanted porch drawing black-and-white spotted cows grazing by the graveyard fence, I pencil in their big heads, kind eyes, tails twitching, swatting flies. On stormy days, inhaling wet sagebrush and the after-rain, I sculpt them in moist gray clay.

Mother’s a nurse at Copper Queen Hospital in Bisbee. Mammaw takes care of us, and when she’s not making cinnamon rolls, gardening, or chasing us with a switch, she chews snuff she calls her consolation, spitting into an empty Folgers coffee can beside her chair while reading her black leather Bible with gold index tabs. Parked at her knee, she teaches me to sing, The Old Rugged Cross, belting out the refrain—lost sinners were slain.

Mammaw’s face glows when singing hymns, but sometimes, wearing her lavender housedress that smells like starch and snuff, she sits by the kitchen window, weeping.

My little sister and I are making mud pies in our new front yard when two airplanes fashioned from Lifesavers and Juicy Fruit gum land at our feet. An old woman in a sun bonnet, peeking through the sweet peas climbing the chain-link fence, says, “Welcome, girls! I’m Pee Wee, your neighbor!” She looks like Mammaw, but shorter and older with leathery sun-scorched skin. She and her husband, Daddy Jim, who always wears overalls, are both in their eighties.

Pee Wee and I traipse through the high desert hunting for fool’s gold and cow chips, as she calls them. We stuff the smelly, lightweight discs in burlap bags and drag them behind her house of tiny rooms to fertilize her flowers and vegetable gardens. She teaches me how to plant seeds in a row, feed infant goats with a baby bottle, and gather Bantam chicken eggs in the dark and musty coop. Daddy Jim makes me laugh when, with eyes twinkling, he lines sweet peas on a table-knife and rolls them into his mouth without dropping even one.

Once a week, Pee Wee dons her flowered-cotton church-dress, we pick the biggest blossoms from her garden, and cross the road to Evergreen Cemetery. “Don’t walk on the graves,” she says. “They’re people under the ground. It’s disrespectful to step on them.”

Lying our flowers on chosen markers, we sit on a large tombstone in the shade of the cypress tree, and she tells me stories about her family members buried there. I can’t remember her exact words, but I can still hear her low-toned voice. I can see her eyes moisten as afternoon shadows shapeshift across the headstones, across her church dress, her wrinkled hands, and face. I can still smell the fragrant base notes of our wilted bouquet, the sweet earthiness of cows and new graves.

That fall, I started kindergarten in the brick schoolhouse at the end of the road built by the Phelps Dodge Mining Company. My teacher, surprised I can name all the colors, encourages my love of finger-painting.

When Pee Wee’s husband dies, my mother takes me to see him at the First Baptist Church in Bisbee but he’s not wearing overalls and doesn’t look like himself. Later, in Evergreen Cemetery, holding Mammaw’s hand, I watch two men lower my friend, Daddy Jim, into the ground and shovel dirt on top of his casket.

Roaming the desert, I collect dead bugs and gently lay them on beds of cotton in empty jewelry boxes, bury them beside Mammaw’s white daisies. I fashion little crosses with twigs and twine and stick them on their graves. I’m not afraid of death. Not yet.

That night, quieter than my perception of quiet, ghosts and tombstones locked behind the cemetery gate, the Milky Way glowing above Douglas Road, I reach for the stars that appear close enough to touch. Suddenly, red lights flashing, an ambulance stops in front of Pee Wee’s house. In my five-year-old wisdom, I know it’s come to take away my friend.

I run inside, plop on the linoleum, cut a red heart, and glue it inside a folded piece of construction paper. Looking back, I believe that night at the age of five, my impulse to give a gift of my own creation revealed an artist’s response to life. Like the poet brings his poem and the gardener brings flowers, the painter brings her picture.

As attendants ease my friend’s frail body into the ambulance, I place my card in Pee Wee’s hands. Flashing red lights disappear. A tumbleweed rolls across the road into the high desert where we hunted for cow chips and fool’s gold. Standing alone on Douglas Road, it seems darker than usual, as if God plucked the Milky Way from the night sky.

![]()

Book I

Desert Journey, 1996, WC, 22×30 inches, Eva Margueriette NWS

1. Summertime

THAT SUMMER OF 1964, my mother’s youngest brother, the one Mammaw called the black sheep of the family, flew the redeye from Beaumont, Texas, to the City of Angels sporting a worn three-piece suit and a thin black Mafia-mustache slicked with Brylcreem.

He came to visit us once in Bisbee. A six-year-old fatherless child, fascinated by his southern drawl and colorful language, I basked in his attention. The last time I saw him, two years later, he came banging on our door late at night and placed a gun on our kitchen table. I remember Mammaw crying, Mother yelling, my little sister, Jeanne, and me hiding under the bed, fearful threads dangling in my face.

“Ya’ look real pretty in high heels,” he said, approaching me after the ceremony. “All grown up.”

Not knowing my mother had invited him to Jeanne’s graduation from Monrovia High School, I thought of him as a flirting stranger.

“Don’t recognize ya’ Uncle Wendell, uh?”

He asked for a ride to the Hollywood Record Store to buy my sister a Porgy and Bess album as a graduation gift. Wanting to impress him, I said, “Sure, I go there all the time.”

I fell in love with Sidney Portiere and the music the night Stuart, my high school sweetheart, took me to the drive-in theater to see the film, Porgy and Bess, inspired by Gershwin’s 1935 opera about racial injustice and addiction, a real-life drama still playing in American cities.

“Summertime’s my favorite,” I said, rummaging through record bins, softly singing Bess’s lullaby, the troubled mother with dreams for her newborn son.

“Ya’ sing like a bird.” Uncle Wendell said. I wish I were a bird, I thought, I’d fly away, be free of all my troubles.

He flashed a wad of $100 bills at the cashier when buying the album. Like all the customers in line, I gaped at his fistful of money. I’d never seen anything larger than a $20 bill in my almost twenty years of living.

Grabbing my arm, he steered me out the door onto Sunset Boulevard, dodging tourists looking for movie stars. “So, ya’ like jazz?” he asked.

“Oh yes!” I bragged about buying Blue Haze, the Miles Davis classic jam with John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley.

“I’m a big fan of the trumpet man,” he said. “How ’bout goin’ to ya’ digs and get’ in the groove?”

Wasn’t I supposed to drive him back to Monrovia?

“Not yet,” he said. “I wanna’ get to know my pretty little niece better.”

Zigzagging through the crowd, holding onto the suited arm of a man I hardly knew, a man old enough to be my father, I caught a whiff of mothballs and danger.

![]()

2. Escape

AT THE AGE OF SEVEN, my mother took me to see Gone with the Wind at the Copper Queen Theater in Bisbee. I imagined myself as Scarlett O’Hara riding the pony, dancing at the ball, kneeling in Tara’s field, shaking my fist at the sky, screaming, “I’ll cry tomorrow!”

Mother’s Scarlett-like black hair and green eyes convinced me of my southern belle inheritance. On that last evening of my years-long crusade to save my mother, I found her, still beautiful at forty-two, standing in the kitchen, nursing a nightly bourbon and Coke in its never-empty blue plastic tumbler, puffing away on her slim, filtered Benson & Hedges 100s.

“Mommy, you have to stop drinking,” I cried. “You’re killing yourself.”

“Mind your own business, young lady. I’ll do as I damn well please.”

I pleaded louder.

She screamed, “Get the hell out of my house and don’t come back!”

She said I ran away from home. I said she threw me out. Homeless at nineteen, Susie welcomed me into her attic apartment in the 1890 Victorian mansion on Carondelet near the art school where we met two years earlier.

When Madame Nelbert Chouinard founded Chouinard Art Institute in 1921, the area surrounding MacArthur Park, known as the Champs-Elysée of Los Angeles, glistened with luxury hotels and Beaux-Arts apartment buildings. Before we arrived in 1961, most of the Art Deco mansions, like our house, were subdivided into one or two-room apartments, and the once luxury hotels rented rooms for $20 a month to derelicts whose only possessions fit inside a paper grocery bag.

To pay rent, I applied for a job at Pomona Tile Company in Los Angeles. Despite my eighty percent loss, the powerful hearing aids I’d worn since childhood, plus my lipreading talent, enabled me to appear somewhat normal during the job interview. When hired as a color consultant, I quit art school.

Looking important, I sat at my showroom desk drawing designs for tile installations and taking phone orders from contractors and clients requesting tile samples. Unable to hear the exact numbers and spelling of names, I often mailed the wrong tile sample to the wrong address. My kind boss did not fire me but laid me off a week before Christmas, which allowed me to collect unemployment.

I reported to the unemployment office every week, took typing tests, and interviewed for jobs. Hired by a furniture store in Canoga Park, I drove all over Los Angeles knocking on doors, drumming up business for the owner, until I realized working on commission cost more in gas than I earned.

Months before Uncle Wendell’s visit, I’d moved downstairs to a two-room flat. Susie and I continued sharing the hall bathroom with Ray, a splotchy-faced wino on welfare who sang Irish ballads while washing his dishes in the bathroom. We considered his shenanigans a fair price for living in what we called the castle with carved oak, gingerbread trim, balconies in every room, and an authentic Tiffany stained-glass window in the entry hall. The once elegant Westlake area reeked of decline, but our young artist’s eyes, prone to illusion, saw only the splendor of its turn-of-the-century façade.

Uncle Wendell swaggered up the wide staircase to my flat, sprawled on the couch fashioned from a twin mattress and Mammaw’s handmade featherbed, propped against the wall, and whipped out his silver-plated cigarette case. “Like a smoke, sweetie?”

“No thanks,” I said, fishing a menthol Kool from my purse. “I have my own.” Lunging across the couch, he lit my cigarette with his shiny butane lighter, its acrid fumes overwhelmed the scent of jasmine wafting in the window from the weedy lot below.

Miles Davis trumpeting Old Devil Moon on my record player, an eighth-grade Christmas gift from my mother, I bragged about sitting in the front row at Shelly’s Manne Hole, the smoke-filled jazz club in Hollywood every Wednesday night. Bobbing my head to the beat of Paul Horn’s Quintet, drinking sugar-cubed champagne Paul sent to my table, leading to a year-long after-hours, casual love affair with the handsome Juilliard-trained musician who was too smart to get a young woman pregnant.

“Really cool jazz is at Preservation Hall in New Orleans where ya’ daddy was born,” Wendell said.

“My father?”

“Yeah, I heard ‘bout his disappearin’ act.”

I longed to visit the birthplace of jazz, my father and grandfather, and ask his estranged parents what happened to him.

In my recurring dream, I’m a little girl sitting on the windowsill, red ribbons braided in my dark brown pigtails, crying, Daddy, Daddy, please come home!

“I dream of going back to art school,” I said, lighting another cigarette. “Maybe get my degree at The Art Students League in New York City.”

“Ya’ gotta’ whole lotta’ big dreams, lil’ lady.”

Tears clouded my eyes. “They’re all spoiled now.”

“What’s wrong, sweetie?”

“I was late.”

Wendell’s dark eyes lit up. The music stopped. I moved away from the window and reset the needle on Blue Haze.

“Late, uh?” A smoke ring rose above his head like a halo. “How’d ya’ get knocked up, baby?”

“It’s complicated.”

I told him I started having sex with Stuart at fourteen. We’d gone steady until I became a wild art student, believing sex was part of the curriculum. In March, I met a drug addict, just released from prison. He only wanted a platonic relationship, which appealed to me since I’d sworn off sex at the time. In late April, he changed his mind and convinced me to share his codeine cough syrup derived from morphine, stole my diet pills, and disappeared the next morning.

A week later, Stuart, whom I’d not seen for a year, took me out to celebrate his birthday. He spent the night. “So, I’m not sure.”

“Busy lady!” Wendell said, rubbing his stubbled chin. “Betcha’ could make a lotta’ money once ya’ stop givin’ it away.”

“What did you say?”

“I said, don’t worry, sweetie.” He grinned, exposing his nicotine-stained teeth. “How ‘bout comin’ to Beaumont with me?”

“Texas?”

“Yeah, we’ll take care of ya’ lil’ problem. Not legal, ya’ know, but I got connections.”

“I can’t. It’s too far from home.”

“How ‘bout goin’ to the Big Easy to find ya’ father. I’ll help ‘ya hunt him down!”

Finding my father sounded like a dream come true. After all, Wendell was my mother’s brother, Mammaw’s youngest son. So, what if they called him the black sheep of the family? I was one too. The drummer riffed behind Miles on trumpet. Black sheep and lost sheep conversed and conspired.

I snuffed out my last cigarette. “And art school?”.

“Ya, betcha! I’ll send ya’ to that fancy school in New York City.”

Mammaw would say it sounded too good to be true. I had no job, no school, no home. I had nothing but my dreams. What did I have to lose?

I searched Uncle Wendell’s eyes for reassurance. “You promise?”

“Sure, I’ll take care of ya’ lil’ girl!” he said, hugging me in what I construed as a fatherly embrace. “We’re family.”

![]()

3. Desert Journey

FOUR $25 UNEMPLOYMENT CHECKS stashed in my oversized purse, and a portable record player, art supplies, Elvis Presley’s gospel, jazz albums, and boxes and boxes of books squeezed in my bronze 1953 Chevy with its wired-on headlight, we fled at dawn.

Driving through downtown Los Angeles, singing, gotta’ travel on, summer’s almost gone, we headed east on Route 66, snaking along the foothills beneath the San Gabriel Mountains, passing my family home in Monrovia. Blinded by the rising sun, hot air blowing in rolled-down windows, heat shimmering off the two-lane highway through Indio and Blythe, we entered the desert.

Near the Mexican border between Bisbee and Naco, where my father left us sleeping on cots in the country club storeroom, a big rig passed us on the two-lane road, shaking the Chevy, sucking us sideways. Headlights glaring. Wendell pointed toward miles of barbed-wire fencing crisscrossing the moonlit landscape. “That’s ’bout where his grave would be.”

“Whose grave?”

“Ya’ father, James Wright Commagere,” he said, flicking fiery ashes out the window. “Wanna’ know what happened ta’ him?”

“Nobody knows,” I said. “Not even his own mother.”

The motor droned. His profile in shadow, he nodded toward the abyss. “Folks say ya’ mama killed him and buried him out there in the desert.”

How could he say such a thing? Even if it was true, which I doubted, it didn’t make sense to say he’d take me to New Orleans to find my father if he was dead.

“Do you believe it?”

He gripped the steering wheel and stared at the rollercoaster dips in the road ahead, lit only by our headlights. “It’s jus’ a theory,” he said.

We parked the Chevy outside the door and slept in separate rooms at the cheap roadside motel. In the morning, I rose up singing, Livin’ is easy. Nothin’ can harm ya’ with Mommy and Daddy standing by, but that second night at another raunchy motel on the I-10, east of El Paso, Uncle Wendell paid for only one room.

Blinded by my desire to escape, I wanted to believe in his promises and fatherly embrace. Did I set myself up by bragging about my sexual escapades? Betrayed by his advances, I didn’t resist. Barely twenty, somewhat childlike and eager to please, I’d learned to detach from my emotions when submitting to men.

Surrender! Elvis’s newest hit blasting on the car radio, we arrived in Beaumont, Texas, at twilight. Across the street from Wendell’s apartment, the malodorous oil field looked like a German Expressionist painting rendered in black and burnt umber.

Wrestling boxes up the outside staircase, I imagined the aroma of southern hospitality, Mammy’s fried chicken, and peach pies baking in the oven, but Wendell’s wife wasn’t home. The welcoming party consisted of three enormous crows picking at weeds in the adjacent vacant lot.

Escaping Los Angeles, singing, summer’s almost gone, blinded by the rising sun, I imagined myself as the damsel locked in the tower and my uncle as Saint George who came to Los Angeles to slay the dragon and set me free.

My knight in shining armor pointed to a mattress on a wire frame in a dungeon-like cell. “Put ya’ stuff in here,” Wendell said. “It’s ya’ new home.”

Outside the bedroom window, the murder of crows screeched, spread their ebony wings, and took to the sky in the dying light.

![]()

4. A Willin’ Doctor

NAUSEOUS, A FAN AT the foot of my bed blowing oil-refined stench in my face, I heard Mammaw say, Out of the frying pan, into the fire.

In the morning, when Uncle Wendell leaned against the kitchen sink, stroking his wife’s reddish hair, she handed him a fistful of $100 bills. Noticing me in the hallway, he said Evelyn worked late. “She’s goin’ to bed, and we’re goin’ out for breakfast.”

Nestled in a coffee shop corner booth, downing apple fritters drowned in maple syrup and powdered sugar, he boasted about his Mafia connections in Little Rock, Arkansas, jail time on a road gang, and a book he’d written, Judge Me if You Dare, recounting his escapades as a sergeant in the US Army at nineteen when he’d escaped from the Germans after parachuting into France in 1944, the year of my birth.

Evelyn, whom my uncle called an old pro, worked all night and paid the bills with cash while he fooled around with me. Wendell sweet-talked me, but I wasn’t a total victim. He didn’t gag or tie me up; I came willingly. Confessing sex with Stuart, my high school sweetheart, and the after-hours love affair with the jazz musician at nineteen, I never mentioned getting anything out of sex except attention, a substitute for the love I craved. My stepfather called me a nymphomaniac, but he was wrong. Unaware that women were supposed to experience sexual pleasure, I assumed sex was all about pleasing the man.

My uncle treated me to lunch at a diner, bought me a new blouse at the strip mall, and took me to his bed when Aunt Evelyn was working. No bars covered the windows in his Hague Street flat, but I never considered escape. That night in the Texas motel on the I-10, I hated Uncle Wendell but later yearned to please him. Basking in his attention, he seemed less sleazy, but I questioned how long I could keep masquerading as the pretty lil’ niece and her doting uncle.

Still young and good at playing make-believe, I pressed snooze on my inner alarm, dressed, adjusted the volume on my powerful hearing aids, surrendered my unemployment checks to Uncle Wendell, devoured Gulf Coast seafood and fried hush puppies, and gained weight pretending to spend summer vacation with my Southern relatives.

“Gotcha a lil’ present, sweetie!” Wendell and Evelyn smoked pot. I didn’t like the bitter taste or smell of the joint they offered me, but I did like the amphetamine pill he brought me because I’d taken doctor-prescribed pep pills on and off since seventh grade for weight control.

The powerful drug kept me awake, writing a ten-page letter to my mother without mentioning being pregnant, but she already knew. Before leaving California, I’d confided in Stuart, and he told her, betraying my confidence.

Apologizing for my angry goodbye, sounding upbeat, I wrote: No need to worry, Mom. I’m being treated like a real lady. We dine out often, and I’m eating way too much. Uncle Wendell says he’d rather buy me furs and diamonds than feed me!

My doting uncle offered to mail my letters, but I learned later, he only mailed this first one to my mother, dated July 3, 1964. He threw the rest of the letters I gave him in the trash, as well as all my incoming mail.

“It’s time to get this show on the road!” my uncle announced two weeks after arriving in Beaumont. He’d found a willin’ doctor, and after the exam in his home office, Wendell burst in exuding his phony charm. Perched on the end of the examining table, hunched over, hugging my hospital gown, I listened to the two men talk about my body and the baby in my womb as if I wasn’t in the room.

Pounding the steering wheel, Wendell raged, “That doctor’s a prick. Stinkin’ coward said he wasn’t willin’ to do nothin’ illegal.”

When he persuaded me to come to Texas, crowing, “Don’t worry, sweetie, I got connections,” the word abortion seemed only a mere abstraction. The doctor’s hands invading my body, pushing on my stomach, made it seem more real.

Wendell found another connection, another prick who said no. He sulked and shouted obscenities at the physician. Maybe finding a willin’ doctor wasn’t as easy as he thought.

“Get prettied up, lil girl!” Wendell said. “We’re gonna’ meet an old friend. In downtown Beaumont, brick buildings built during the early 1900s oil boom lined Crockett Street. “Fanciest whorehouse in all a’ Jefferson County,” he said, pointing to the Dixie Hotel. “Until the madame got caught bribin’ the police chief.”

Suddenly, we ducked into an unmarked door beside a hardware store and climbed a narrow flight of stairs. Welcomed by a blast of cool air, Aunt Evelyn welcomed us into a quiet hall of small rooms and sat us in a parlor furnished with Queen Anne chairs and red velvet drapes.

A full-figured woman appeared in the doorway. “Isabella!” Wendell said, turning toward me. “This, my dear, is the boss.”

Her auburn-dyed hair, twisted, pinned, and piled high on her handsome head, the procurer of the Beaumont brothel looked like the Moulin Rouge madam stepping out of a Toulouse Lautrec painting.

“Happy to meet you, miss,” she said, clasping my hands. I liked her right away.

My uncle often dropped me off at Madam Isabella’s elegant, air-conditioned home, where Georgia, her warmhearted maid, served me iced tea and salad on Desert Rose, Franciscan dinnerware in the library. Escaping the heat, I read art books by Cezanne, Mary Cassatt, and Braque, painters I’d studied at Chouinard Art Institute, and devoured Edgar Cayce’s There Is a River, and volumes on religion, spiritualism, talking to angels and guides, and the afterlife, seeking answers to my urgent questions about the wheel of suffering, life, and death.

Wendell tracked down another connection eighty-five miles from Beaumont. In a high-rise office building in Houston, we crowded into the waiting room with other expectant mothers who were married to the fathers of their unborn babies and had homes and health insurance. After a quick exam, the doctor agreed to perform an abortion for $500, but he warned that the first-trimester deadline loomed weeks away. “Time’s running out.”

“Well, sweetie, we hit the jackpot!” Wendell crowed, standing side by side on the sidewalk seeking shade in the shadow of the skyscraper. “Too bad, I don’t got that kinda’ dough.” I wondered what happened to the $100 bills Evelyn brought home every morning.

“Ya’ know anybody who’d help us out?”

I thought of Stuart. One of five children whose mother worked in a Pennsylvania shoe factory and whose father was often unemployed, he resolved to someday own a home and have a steady job. After graduating from high school, he served a four-year apprenticeship at the Monrovia Daily News Post, and he now worked full-time as a journeyman printer with medical insurance and overtime pay.

‘Maybe Stuart. He has a good job.”

“Yeah, girl, give him a call!” Wendell said, handing me a stack of silver quarters. I slipped into the lobby’s wood-paneled phone booth and pressed the receiver against my better ear. Unable to decipher the operator’s high-pitched instructions, I closed my eyes, and like a dog, focused not on her words, but on the tone of her voice and kept dropping quarters in the slot until I heard the soothing sound of, “Thank you,” and she dialed the number.

Hearing Stuart’s voice, familiar and soothing, forgetting we broke up, because of our unreconcilable views on everything, I wanted him to fly to Texas and take me home.

“I’m in Houston,” I said. “And I need money.”

“How much?” His voice sounded willing.

“A doctor agreed to an abortion for $500.”

“Really?” His tone of voice suggested shock or perhaps sarcasm which he often confused with humor.

“Can you send me the money?”

“No. No way!” Before I could ask why or say goodbye, he hung up.

Maybe he didn’t believe in abortion. We went steady for seven years, but I never questioned his belief or my own. At fifteen, terrified every month I might be pregnant, I asked Stuart, “What would we do?

“Don’t worry,” he said. “We’ll get married!”

Wendell stood outside the booth waving his hands. “Get on with it!” I read his lips.

I held the receiver, listening to the dial tone, letting the word, no sink in.

“Stuart said no.” My uncle’s face burned red as if on fire.

“We’re comin’ back soon as we get the money!”

We drove home in silence. Approaching Beaumont, the sun sinking red-orange behind the black oil derricks, Wendell got his voice back.

“Bout time we made that lil’ trip to New Orleans, I promised ya’.”

![]()

Mardi Gras Masks, 1992 WC, 15×19, Eva Margueriette NWS, Kommerstad collection.

5. New Orleans, 1964

All that we see or seem is but a dream within a dream. ~ Edgar Allan Poe

“TIMES RUNNIN’ OUT,” WENDELL said, parking in front of Midge Mother’s house on Constance Street. “You gotta’ ask your grandparents for the five hundred bucks.”

It seemed wrong to ask. I’d never met Louis Commagere, my father’s father. My connection to Midge consisted of an annual shipment of Mardi Gras beads, plastic doubloons, and boxes of leather-bound books inherited from her mother, given to my father, and passed on to me with her elegant handwriting on the first page: To James Wright Commagere, from your loving mother, Margueriette Strother Boesch.

A crabby face peered through the peephole. My grandmother unbolted several locks and ushered us into a dark hall stacked with newspapers, waist-high. We followed her short, plump body up the narrow staircase. She introduced me to her upstairs boarder as Eva Margueriette, my granddaughter, an artist from California, as if I were a Hollywood celebrity,

“This crystal chandelier hung in the Morganza Plantation during the Civil War,” Midge said, gazing nostalgic at the relic hanging in the downstairs parlor. “Your great-great-grandmother, Margueriette Aurora Falconer, gave it to my mother.”

Oil-painted portraits of Confederate soldiers hung like ghosts above the baby grand piano caked in dust. Leather-bound volumes, like those she’d sent me, lined the bookshelves. When I told her how much I cherished those books, her crabby scowl softened to a satisfied smirk.

At eleven, attempting to read Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Lord Byron: Poems, and The Raven by Edgar Allen Poe, but unable to decipher their meaning, I fell in love with the sound of the words and font design. Most of Midge’s antique books remained packed in cardboard shipping boxes and stored in our basement. My heart still hurts remembering the day the basement flooded and destroyed my precious books.

In seventh grade, I discovered Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Essay on Friendship in a small red volume that survived the flood, tucked on the living room bookshelf. Profoundly hard of hearing, overweight, and without friends, I learned, in studying the essay, that the only way to have a friend was to be one.

Reading his essay on Compensation in high school, I found a friend in Emerson, and as an art student seeking spiritual guidance, Self-Reliance became my lodestar. Such advice as Trust yourself; vibrate to that iron string within you, continues to inspire my creative life.

Charming Midge Mother over a cup of chicory-laced cafe au lait, Uncle Wendell suddenly bolted for the door. “I’ll come back to get ya’ next week.”

Next week? What about his promise to help me hunt my father down? Pleading my case, I followed him to the curb. He slid behind the wheel, revved the motor, and drove away in my Chevy, scowling, “Don’t ya’ dare come back empty-handed!”

“You cook them live in boiling water.” Midge Mother nodded toward the ten-legged crustaceans piled on the kitchen table, covered with newspaper.

Did they cry when they died? I asked, staring at the crab’s orange eyes.

She shook her head no. Sighing, she said she wanted me to know she didn’t blame me for what my mother did. Did she mean when Mother remarried? “No!” Midge said, “It was the adoption.”

The Mardi Gras trinkets stopped coming that year I turned eleven, the year Lee adopted us, and the court deleted Commagere from our birth certificates as if our biological father never existed. My grieving grandmother could bequeath her Civil War portrait paintings and crystal chandelier, but my mother had stolen her dream of passing on her only son’s proud name.

“Midge Mother,” I said, wiping my hands on the smelly newsprint. “Do you know what happened to my father?”

“No,” she said, dry-eyed like the crabs who died. “I never heard from him.”

Did abandonment run in families like inherited genes, or sins of the fathers passed from generation to generation? Jimmy, her only child, deserted us in my fifth year. My father was five when Midge divorced Louis after catching him in an affair at the Monteleone Hotel frequented by Faulkner and Tennessee Williams, and if Uncle Wendell’s plan succeeded, I’d be next in line to abandon my child.

“I’m pregnant,” I said, setting my pincer and hollow crab leg on the stained newsprint. Midge Mother smiled. I detected a gleam in her eye at the prospect of a great-grandchild, a girl perhaps, another Margueriette.

I wish I’d kept my mouth shut, said Good night, Grandmother, and left her to her reverie, but with Wendell’s voice screaming, Don’t come back empty-handed, I said, “I’m sorry, but I must ask. I need $500 for an abortion.”

Her smile collapsed into a thin, hard line as she turned and fled the kitchen without another word.

The following morning, Midge averted eye contact but had arranged for me to meet my grandfather. “You’ll need this,” she said, handing me a black umbrella. Sloshing through a downpour, I boarded a bus departing for the French Quarter in New Orleans, the birthplace of my father, grandfather, and great-grandfather. Rain splattered on the window, passing green-shuttered, columned-façades and wrought iron balconies, where, for two centuries, young damsels leaned over the railings, exposing their breasts, delighting Mardi Gras merrymakers.

Asking strangers for directions led me past the Monteleone, where my grandfather had been caught in the act, to his real estate office on Royal Street. Louis Commagere lorded over his desk like a tall toad. His brown eyes and chiseled chin bore a resemblance to pictures of my father in his Army uniform.

“It’s nice to meet you, grandfather.”

He nodded. His eyes remained focused on the Shaeffer pen he manipulated between his long fingers like a sleight-of-hand magician. I wanted to scream; I’m your own flesh and blood. Why aren’t you happy to meet me?

Perhaps he wasn’t into small talk. “I came to ask you,” I said, deciding to get to the point of my visit. “Do you know what happened to my father?”

“I got a postcard from him,” he said, looking up as if seeing me for the first time. “About ten years ago.”

“Ten years?” I collapsed in the chair by his desk. Uninvited.

“Yeah, postmarked, Brazil or Argentina. Somewhere in South America.”

With or without Wendell’s help, I couldn’t go that far to hunt my father down. Rain beat on the roof. The office smelled like new graves, damp and moldy. Why had he kept their only son’s whereabouts a secret from Midge and not informed my mother, who’d reported him a missing person and never received child support?

“Is he alive?”

“I don’t know,” he said, still fiddling with his fountain pen. “Never heard from him again.”

Expecting the pen to disappear from his nimble fingers any minute, I stood to leave. Ya’ gotta’ ask ya’ grandparents for the money. Don’t ya’ dare come back empty-handed! Wendell’s warning acted like a hypnotic suggestion. Afraid to ask but afraid not to, I told my estranged grandfather I needed $500 for an abortion.

“I don’t have that kind of money lying around,” he said.

I was eight when my mother told me, “Your grandaddy’s rich! He owns a drug store and lives in a big house on Lake Pontchartrain.” I wondered if the story was a true once upon a time, or a fairy tale fueled by her wishful thinking.

“But I am a registered pharmacist!” Louis said, suddenly vanishing behind a curtain in the corner of his office. Reappearing moments later, the alchemist handed me a glass of water, and three pink pills cushioned on a Kleenex. “Take these,” he said. “They might do the trick.”

I never thought to say, No, thank you, or ask about possible side effects of his elixir, but suffering no symptoms the following day, I suspected the not-so-friendly family pharmacist lacking a magic potion had prescribed pink baby aspirin.

The next night, Louis Commagere’s six brothers, who bore no resemblance to my grandfather, invited me to a family dinner as their guest of honor. Admiring the fine china and crystal goblets, I imagined my mother sitting at the same table with my father’s uncles, and his grandparents affectionately called Mère and Père when she brought me to New Orleans for my first and last visit twenty years ago.

These kind relatives, still mystified by my father’s disappearance, remembered Jimmy as a mischievous youngster and chef-in-training at a local five-star hotel before he married my mother and served in the war.

Perhaps taking pity on an abandoned child, my great uncles treated me to a week of nightly dinners in fine restaurants, sampling New Orleans cuisine: Oysters Rockefeller, gumbo, red beans, and rice. Grateful I didn’t have to ask them for money; I kept my secret.

New Orleans, February 1944, scrawled on the back of the only photo taken with my parents, captures my father, tall and handsome in his brown wool Army uniform, smiling at the camera. He’s standing beside his wife, Evelyn, twenty-three, wearing high heels, and war rationed, black-seamed nylons, holding me wrapped in a baby blanket. They stand, posing in front of Saint Louis Cathedral, where at six weeks old, I’d been baptized Eva Margueriette Commagere and sealed as God’s own.

Believing she’d married into a wealthy, prestigious New Orleans family, my mother, raised with six older brothers by their widowed mother on a farm in Lubbock, Texas, idolized her new mother-in-law, Margueriette, a divorcée who lived in the French Quarter with antebellum antiques and a baby grand piano.

Like the sins of the father, my mother, meaning no harm, wanting only blessings for her firstborn child, had passed her fantasies on to me. I knew Mammaw would say, You’ve been chasing rainbows, and my quest to find my father, nothing but a pipe dream.

6. Leaving New Orleans

BUDDY, A HANDSOME, GRAY-HAIRED gentleman, an old friend of my great uncles, joined us for dinner in the French Quarter on the eve of my departure.

Following nightcaps and French farewell kisses on both cheeks, Buddy offered to drive me to Midge Mother’s. Seeking a surrogate father in every man I met, I basked in his firm but gentle touch, holding my arm, guiding me through the after-dinner crowd to fetch his car keys from the hotel room.

I sat on his double bed. Waiting for him to find his keys, old tapes playing in my mind, I assumed he must be like most men I’d known who paid for my dinner and set the stage; I knew what to expect.

“No, no, miss,” he said, seeming to intuit my thoughts and flawed assumptions. “I’m a married man with five children. My youngest daughter’s your age and beautiful—like you.”

His gentleness unleashed months of pent-up tears and emotions. Sobbing, I told Buddy my uncle dropped me off at my grandmother’s last week to find my father, who disappeared fifteen years ago, and I was almost three months pregnant and afraid to go back to Texas tomorrow without the money for an abortion.

“You don’t want to do that, young lady,” he said, handing me a box of Kleenex. “Children are precious gifts from heaven.”

I didn’t have a husband or a job. I didn’t have a choice, but Buddy insisted I always had a choice. Wiping my tears, he said to go back home and have this baby, but I didn’t have a home, and my mother didn’t want me.

“Don’t worry, my dear, God can make a way where there is no way.” I wasn’t sure what he meant, but that night, driving through New Orleans with Buddy, I knew what it felt like to have a father.

Passing Commander’s Palace on Washington, where my great uncles treated me to Sunday brunch, parmesan-crusted oysters, and brandy punch, we turned onto Carondelet St. north of St. Charles. I spotted a restored Victorian mansion, a replica of our dilapidated house on Carondelet in Los Angeles, two thousand miles away.

“How’s it even possible?”

“Life is full of infinite possibilities,” Buddy said.

Driving north along the Mississippi River, where Irish immigrants worked the docks at the turn of the century, we arrived at Midge Mother’s house on Constance Street. A full moon hovered like a wraith above her beloved magnolia tree. The stars winked. Buddy opened the wrought iron gate. Holding my elbow, he escorted me to the porch and rang the doorbell. Like a guardian angel, he stood beside me until my grandmother peered out the peephole and unlocked all the deadbolts.

I hugged him. “Merci beaucoup!”

“Have a safe journey home,” he said, stepping off the moonlit porch. “I’m praying for you.”

I turned to wave goodbye, but like a dream within a dream, he’d vanished.

7. Return to Texas

Uncle Wendell had called at the end of the week and said he wasn’t coming back as promised, and to take the bus; he’d pick me up at the station.

Nauseated by diesel fuel, I boarded the late-night Greyhound destined for Beaumont. Hugging my bag in the crowded aisle, a large dark woman motioned to the empty seat beside her. Her soft eyes comforted me on the pitch-black roads of southern Louisiana.

At four in the morning. I arrived at the deserted Beaumont station to more nauseating fumes and broken promises. Uncle Wendell, a no-show, I took a cab to his apartment to find the front door wide open, and all the lights turned on. I sat on the landing in a plaid, plastic-webbed lawn chair.

Awakened, blinded by the sun, two men in gray suits loomed over me, nudging my shoulder. “Detectives, ma’am. Beaumont police,” the taller man said, flashing his badge in my face. “Ya’ Wendell Young’s niece?”

I nodded.

Like Sergeant Friday on Dragnet, the shorter detective with the bulldog face said, “We’re takin’ ya’ in for questioning.”

Corralled into the back seat of the police car and ushered into the station interrogation room like in Perry Mason, another favorite weekly TV drama, the bulldog said, “We arrested your aunt for pro-sti-tu-tion, and your uncle on the Mann Act.”

I pictured a one-man act like a trapeze artist in a circus, but he said it was a law named after Congressman Mann that made it a federal crime to take a woman across state lines for prostitution.

The tall officer leaned closer, reeking of aftershave. “You know your uncle’s a pimp!”

“No, sir.”

I knew what Wendell was up to, but I’d never heard the word pimp in my life. The short, burly-faced detective barked, “Is ya’ uncle pimping you, too?”

Tears dripping off my cheeks, I shook my head. The bulldog raised his eyebrows. The tall, thin detective grabbed my arm. “Let’s go, young lady.”

I thought he was taking me to jail. Instead, he drove to Wendell’s apartment on Hague Street, opened the car door, smiled, “Take care ya’ self, miss.”

I don’t know why they let me go, maybe because I was so young, somewhat innocent, and honestly confused.

Freed from jail, Evelyn showed up later, abrupt and businesslike. She said we must raise bail money for my uncle’s release. I surrendered my last two weeks of unemployment checks. She wanted more.

That night, on a wooden dance floor in a sleazy Texas bar, my aunt made a deal for me to have sex with some old man. Led behind a curtain into a dimly lit closet space cluttered with buckets, mops, and an army cot covered with a clean white sheet, I didn’t have to undress. I shut my eyes. I held my breath. It only lasted a few minutes.

The next morning, soon after arriving at Madame Isabella’s home, I asked her why my aunt had disappeared into a bedroom.

“She’s turning a trick with the bail bondsman,” she said. “To get Wendell out of jail.”

Waiting in the library reading Edgar Cayce’s There is a River, I pondered the principle of cause and effect in science and art, choices that determine our destiny, and Mammaw’s Biblical quote, “As ye sow, so shall ye reap.”

Was God a punishing God or a loving Father? If I had an abortion, would He condemn me as a sinner or not? Either way, I’d experience the consequences of my decision.

Buddy said, “You always have a choice.”

The three-month deadline passed. I could rage against what I couldn’t control or choose to accept my fate. I’d heard about unwed mothers who surrendered their babies for adoption. Perhaps I could bless a childless couple with my gift. For the first time, I accepted giving birth to a child I could not keep.

Determined to escape before Evelyn raised the bail and set my captor free, I considered driving home alone 2,000 miles across the country, but she had my car and keys, and I had no money for food or gas.

I closed the library door and phoned Stuart. Instead of money, I asked him to rescue me. This time, he said yes. He agreed to fly to Beaumont and drive me back to Los Angeles.

Uncle Wendell had lost his phony charm, his anger palpable. Bailed out of jail the day Stuart arrived, my departure resembled a hostage exchange in a war zone. Twenty-four and nervous, my rescuer helped me reload my books, art supplies, jazz albums, and record player in the Chevy. Neither my aunt nor uncle offered to help, nor did they honor our family tradition of providing ham sandwiches and a thermos of coffee for a long journey into the desert.

Destined for California, the land of milk and honey, I slept most of the way, too tired to think about the recent past or the road ahead.

8. What Child is This?

THE HEAVY OAK DOOR groaned like an elderly woman on her deathbed. The century-old Tiffany stained-glass window stolen by vandals from the Victorian mansion on Carondelet left a gaping hole in the entry hall. At the top of the wide staircase, I passed the room where I conceived my baby, and Uncle Wendell wooed me to Texas months before and knocked on Susie’s attic door. “There’s no place in the inn!” she said. “Our beloved castle is destined for demolition.”

My final unemployment checks paid for groceries, a phone, my $35 car payment, and a month’s rent on an apartment in Mar Vista, near Santa Monica. Arranged like motel rooms on a black asphalt parking lot, without stained glass windows or night-blooming jasmine, each cubicle had a tiny bedroom, kitchen, plastic beige coffee table, and a tan couch crying for orange accent pillows.

My car unpacked, I drove to my mother’s house. Mammaw lay in a rented hospital bed in the dining room. In the afternoon sun, her hair that I’d braided, crossed, and pinned high on her head since kindergarten, glistened like a silver crown. My tears dripped onto her face, but she didn’t open her eyes.

I came too late to sing The Old Rugged Cross together one last time, too late to ask questions about the birth of her seven children and the two lost in her womb, too late to beg her forgiveness for the pain I’d caused. As if she waited for me to come home to say goodbye, she passed away the following morning at seventy-six.

On the day of my birth, she’d asked God to let her live to celebrate my eighteenth birthday. Five years before, when an ambulance whisked her away, afraid she’d die, I fell on my knees and prayed, “Please, God, grant Mammaw’s wish, and I’ll dedicate my life to You.” I had promises to keep.

Except for Wendell, all her sons and wives came to the Masonic cemetery in Fresno and buried Mammaw under a big tree I knew she’d like. They didn’t sing her favorite hymn, but in my mind, I heard us singing, on a hill far away stood an old rugged cross, ending with our yelling—lost sinners were slain!

Mother, my sister, and my aunts, exchanging looks, stared and whispered. Talented at lip-reading and body language, I didn’t need to hear their words.

A month after we returned from Texas, Stuart stood at my door, holding bags of groceries. “How about cooking meatloaf and mashed potatoes?” he asked, emptying hamburger, potatoes, canned tomatoes, and a box of Wheaties, my mother’s alternative bread crumbs, onto the beige kitchen counter. I started chopping onions.

Mona, his sister and my friend since I began dating her brother at fourteen, needed me to babysit her three boys in exchange for a place to live. How did she know the unemployment checks stopped coming, and my rent due? Grateful tears welling in my eyes, I remembered that last night in New Orleans, six weeks before, when Buddy said, “Don’t worry, my dear. God can make a way where there is no way.”

Moving thirty-five miles east of Los Angeles to my new home in Upland, a sprawling tract of affordable homes built in the 1950s, I helped Mona get her rambunctious boys, Larry, six, Jimmy, eight, and Ricky, ten off to school, cooked meatloaf with breadcrumbs like her mother, Hawaiian pork chops, and lima beans, napped, and read Paramhansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi. Books seemed to find me when I most needed them. Yogananda’s classic enhanced my curiosity about the mysteries of life and death.

Needing to pay my $35 monthly car payment, I became an Avon lady. The cosmetic company required that I wear business attire even in hundred-degree heat and contact every customer in my assigned district every thirty days. Six months pregnant, I squeezed into my beige pantyhose and too-tight clothes, parked in the shade, and, lugging my Avon bag with samples and sales slips, knocked on every door in Upland’s most impoverished neighborhood.

Sales demanded perseverance. When selling Girl Scout cookies and Job’s Daughters’ Christmas fudge, door-to-door, I learned it took, ten Nos to get a Yes. I needed only to keep knocking, keep my goal in mind, and swallow the pain of rejection.

Not knowing my hunger for companionship and authentic Mexican food, a young Avon customer invited me into her home for lunch. Eating tacos and refried beans with her children outshone Oysters Rockefeller on Bourbon Street.

In early December, another customer with soft wrinkles and shiny gray hair invited me into her modest home with a thick maroon wall-to-wall carpet. Sinking my weary body into her plush sofa, she handed me four boxes gift wrapped in For Your Baby Shower paper with attached baby rattles and yellow duckling diaper pins. Ripping open boxes like a child on Christmas morning, I found a yellow blanket trimmed in satin, newborn T-shirts, a baby bib, pajamas, and cotton receiving blankets decorated with paintings of Peter Rabbit.

“When’s the baby due?” she asked, folding the doll-sized pajamas.

“Seven weeks,” I said, hugging the plush yellow blanket that smelled like violets after a summer rain. “The end of January.”

“Is your husband excited about being a father?”

“Oh, yes,” I lied. “But he’s, uh—he’s in the Army.”

“I hope he’ll be home in time for the birth of his baby.”

“Me too.” Remembering Mammaw’s embrace when I’d scuffed my knees and cried for Band-Aids, I wanted to crawl in the kind woman’s lap and tell her there would be no shower and her beautifully wrapped boxes, the baby’s only gifts.

“Thank you,” I said, gathering the presents, holding my tears lest they escape before I reached the door. “I can’t tell you how much this means to me.”

Depictions of Madonna and her newborn baby on cards and stamps, and in crèches, and pageants of Mary and Joseph reaching Bethlehem in time for the miraculous birth, angels singing, What Child is This? and the words, wrapped in swaddling clothes, made me weep.

Dr. Brower, our family physician had arranged an adoption with a family I would bless with my gift. In the throes of birthing a child I would never know, I denied my feelings, a talent I perfected many years later when coping with emotions too painful to bear.

I managed to mute my mind, but my body refused to be silenced. On Christmas Eve, stepping out of the fragrant Avon Skin-So-Soft bath, I discovered a colorless fluid leaking from my breasts.

Mona said she told Stuart, it’s too hard for a woman to give up her baby. “Don’t let her do it.” Did she mean he should marry me?

Mismatched and too young, we started our rocky relationship in high school. My attending art school widened the gap. I discovered a bigger world of creative people with varied interests who loved learning. Stuart liked watching sports on TV and drinking beer, which he drank all the time and always too much. I loved books. He bragged about reading one book in high school, The Virginian. I enjoyed foreign films, classical music, gospel, and jazz. He preferred playing pool at the bar and listening to country western music. He golfed once a week, I wasn’t athletic. I loved of art, philosophy, and pursuing a spiritual path. He wasn’t interested.

Parked in Mona’s driveway on Christmas night, colored lights strung on the roof, Stuart asked, “Do you want to get married?”

“Not like this!” My bulging body sank further into the leather seat of his Oldsmobile Super ’88. I didn’t want what Mammaw called a shotgun wedding,. “Let’s decide after the adoption.”

“It won’t make any difference,” he said. “I’ve always wanted to marry you.”

Inhaling his familiar Old Spice aftershave and clean starched shirt his mother ironed, I thought about how he flew to Texas, rescued me from the fire-breathing dragon, drove me across the desert, found me a home with Mona, and now at the zero hour, offering to rescue me again.

He didn’t say I love you, but I knew he did.

The responsibility of a wife and baby might help Stuart grow up. Maybe he’d even quit drinking. If we got married, I’d be indebted to him for the rest of my life, but I could keep my baby.

He said, he had one request, he wanted to tell our families he was the biological father. I’d assumed late April, the date of conception and the drug addict responsible, but Stuart spent the night after his birthday dinner, May 7.

“I hoped you’d get pregnant that night,” he said. I didn’t identify his wish as a control thing. Not until years later when he kidded that he wanted, to keep me barefoot, pregnant, and in the kitchen did I begin to understand.

What was a father anyway but a man who cared enough to give an infant his name and stick around? My biological father didn’t love me enough to stay. I wished my mother had married a man who wanted us. In the big picture, what did genetics matter?

On that cold winter night huddled in the car bathed in Christmas lights, we made a pact, a family secret that we’d keep for fifty years. I kissed Stuart on the cheek and said yes.

- Till Death Do Us Part

NO ORGAN MUSIC, BRIDESMAIDS, or virgin bride walking the aisle in full-length white satin, and translucent veil approaching her groom in glorious expectation. A virgin at fourteen, when Stuart said he loved me and claimed me as his own. Though my sins be like scarlet, perhaps entering the sacred rite of marriage they shall be made white as snow.

My mother, invited to the wedding, contacted Dr. Barton, canceled the adoption, and said we could stay in Mammaw’s old bedroom until we got our own place. I want to write the scene, revisit in detail, the moment we hugged and forgave each other, but such reconciliation never occurred. Her offer to shelter our new family and my acceptance amounted to a truce.

We invited twenty-five guests: aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters, our parents, and Stuart’s bar buddies. He bought a keg of beer. I bought pink rosebuds and baby’s breath. Mona sewed me a baby-blue satin, empire-waisted wedding dress. She rented folding chairs from the local mortuary arranged theater style in her living room. Dr. Bryson performed the ceremony, the minister from the Claremont Church of Religious Science, where attending weekly, I sang Let there be peace on earth and let it begin with me, and Kumbaya. On the ninth of January 1965, the day after my twenty-first birthday, two weeks before our baby was due, Stuart, twenty-four, slid Mammaw’s wedding ring on my swollen finger and I vowed to love, honor, and obey him, ’til death do us part.

Not knowing the word spoken only by the new wife and seldom used since Women’s Suffrage, I never questioned my vow to obey.

Mona baked a wedding cake and bought twenty-fifth-anniversary napkins, the only ones she could find. Her mother helped prepare a feast: turkey, ham and cheese platters, and coleslaw with pineapple. We had no need of water turned to wine. The keg of beer, bottles of Vodka, Scotch, and my mother’s drink of choice, Jack Daniel’s and Coke, crowded the kitchen counter. Mother, my stepfather, the groom, and all his bar buddies got drunk.

“The baby dropped! The baby dropped!” An old aunt screamed, pointing at my stomach. The guests gawked, “She’s going into labor! Call the doctor!” Stuart’s mother, who birthed five children convinced everyone it was a false alarm.

At midnight, we departed for our honeymoon at the Starlight Motel on Route 66 in Azusa. The neon sign flashed florescent pink and green, on and off, on and off, Welcome! Vibrating beds in every room.

Eighteen days later, on a warm Santa Ana windy morning, the baby dropped. My water broke. Mother drove me to Monrovia Hospital where she still worked as a surgery nurse before being fired for drinking while sterilizing instruments in central supply.

We found Stuart eating lunch with his fellow printers in Library Park across the street from the Daily News Post. I begged him to come with us. He said he’d come after work.

An hour later, his face scrunched, mouth wide open, screaming, Dr. Brower held him by his feet, and said, “It’s a boy!” The afternoon sun glowed in the window as the nurse rolled me off the gurney onto a hospital bed. I relished lying on my stomach for the first time in months before she turned me over and laid my baby on my stomach, moist skin to skin. I marveled at Terry’s tiny hands and fully formed fingernails. She said we needed to trim them, or he’d scratch his face.

Already celebrating, Stuart arrived at the hospital and carefully signed his first, middle, and last name on the birth certificate. The nurse asked if he wanted to have dinner in the room with his wife.

“Please stay, Stuart, the food’s delicious.” I knew the chef. She’d taught me to cook Hawaiian pork chops during my seventeenth summer working in the hospital kitchen.

“Sorry.” He grinned, proudly producing a box of Cuban cigars. “I’m on my way to the bar to pass these out. 12-27-25

![]()

Self-Portrait, 1972, 30×36 inches, oil on canvas by Eva Margueriette

10. Painting a Self-Portrait

Value your inner life. The Holy Grail of the unconscious mind is like an ocean

that can be fished for enlightenment and healing. — Carl Jung

A FOLGER’S COFFEE CAN brim with turpentine, three long-handled bristle brushes and a palette puddled in pigment crowd the counter. Standing in the dimly lit kitchen, I draw Eve, whose name and guilt I share, on the large cotton canvas as my children sleep.

Rendering two vertical lines, I create a beam of spiritual light illuminating my mind, exposing the diabolical snake coiled at my feet. Applying tinted cadmium yellow, I imagine the light’s radiance turning demons to dust. Horizontal lines drawn across the verticals establish the horizon and the skeletal structure of the composition the way bones support the body

Painting the Tree of Life in my Garden of Eden, diagonals dart across the picture plane in cubistic female forms, whirling masses, flesh and blood, I see Eve’s nude body as my own, who birthed a baby boy named Terry when barely twenty-one.

Warm and cool colors layered against rich neutral tones, shapes and forms appear on the canvas without my conscious intention. Head on and in profile, my face emerges in multiple views, an idiom the Cubists considered a more truthful portrayal of reality.

I’m ashamed of not living up to my own expectations, nor those of Mammaw, my saintly Southern-Baptist grandmother who taught me to sing The Old Rugged Cross, an emblem of suffering and shame!

Seeking the Holy Grail of my unconscious mind, waiting for my husband to come home from the bar, inhaling turpentine fumes, chain-smoking, painting my self-portrait in the narrow kitchen becomes a nightly dance. Stepping in, smoothing one spot of color next to another, stepping back from the big canvas to get a more objective view, my guilt and self-condemnation fade. Eve’s face, my face appears peaceful.

Even the maligned serpent looks friendlier.

An artist seldom knows when a painting’s finished. Needing validation, I made an appointment with my new teacher and mentor, Mr. Claude Ellington. In saying an artist should paint a self-portrait every year, he’d encouraged me to tackle the project. He’d recently helped me reclaim my art spirit after a five-year hiatus. Soon after graduating from Cal Arts, I said my young children needed a full-time mother and stopped painting., but I lied. I quit what I loved because I believed I wasn’t good enough to be a real artist.

Propping my wet canvas on his studio easel, Mr. Ellington suggests we sit far across the room, reminding me of the importance of getting back from a large canvas to see it objectively. I admit to standing too close to my work those many nights painting in the tiny kitchen.

“I recognize the model, Eva. What’s it about?”

“Sin and guilt,” I say.

A quizzical grin flashes beneath his beard. “Tell me about the cross in the painting. It looks like Eve’s carrying a cross or leaning on it.”

I step in to get a closer look. Confused, I step back to get a more objective view. Suddenly, I see the cross for the first time. “Oh, my God!”

It was there from the beginning.

The nimbus ray of spiritual light entering the top of my head has become the vertical beam of the cross, the horizon line its horizontal. No longer an emblem of suffering and shame but of transformation, the cross intersects near my heart, the heart of Eve that sang on the first day of creation. I’m not guilty, not banished from the Garden of Eden as I believed, but remain as God created me, standing radiant in the light of paradise.

![]()

Many years after I painted my self-portrait, I learned it was the Israelites who deemed the metaphorical serpent threatening and masculine, but in mythology it represented the feminine. Because of its capacity to shed old scales and form new ones, the snake symbolized not Satan, but rebirth, regeneration, and redemption.

![]()

Book II

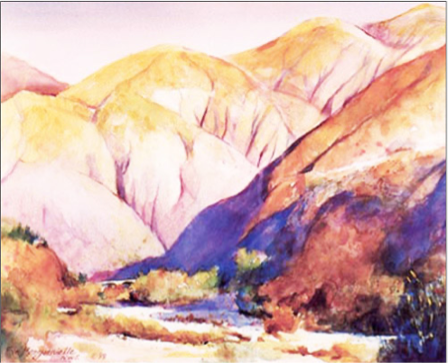

San Gabriel Mountains,1998, 22×20 WC,

by Eva Margueriette NWS, Kommerstad Collection

1. Rites of Passage

The sins of the fathers are to be laid upon the children–William Shakespeare

THE DEVIL SANTA ANA blew in last night from the upper Mojave desert fanning wildfires and suicides and ripping branches off our century-old, blue-gum eucalyptus standing sentry too close to the house. Oblivious to my gratitude the trees hadn’t crashed through the roof, Terry and Melissa ate ketchup-smeared egg on an English muffin, grabbed their lunch box, and ran off to Royal Oaks Elementary.

Preparing for my upcoming one-woman exhibition, I’d spent the day working on a large painting, A Tribute to Pablo Casals. When the phone rang in my kitchen studio, I dropped my brush on the palette, removed my powerful hearing aid and pressed my ear against the receiver on my amplifier phone. “It’s Mrs. Strong,” my son’s fourth grade teacher said. “Did you know Terry’s been absent for two days?”

“That’s impossible! I watched him leave. He took his lunch box.”

“There’s more,” she said. “We caught him smoking in the bushes with a sixth grader named Alex.”

“Alex?” More than eucalyptus trees falling on the house, I feared our next-door neighbor’s influence on Terry since the boys jumped off our roof last summer.

I told my husband what happened and that we had a conference with his teacher the following morning. He left to work his swing shift and I retrieved Terry from the principal’s office. Tears flowing down his cheeks, he promised not to lie again. He and his sister, Melissa ate hot dogs and tater tots and went to bed early. All night, the wind howled like a hurricane on dry land slapping eucalyptus branches against the roof.

I never found out what he and Alex did those two days. Looking back, I suspect I didn’t ask because I didn’t want to know

The bedroom curtains drawn against the morning light; Stuart’s thin five-foot-nine frame clad in blue checkered boxers sprawled across our queen size bed. His eyes clouded. His body reeked of stale beer. I touched his shoulder. “It’s time to go.”

“I’m not going!” he said, pushing me away.

“You have to come with me, I promised the teacher.”

“Nope!” He pulled the sheet over his head. “I’m too tired.”

“Dammit, Stuart, I’m tired too!” I screamed and slammed the bedroom door.

In the bathroom, I applied mascara to hide my fatigue, wriggled into flesh-toned pantyhose and a too-tight pleated-skirt bunched at the waist.

Walking to my children’s school, fuzzy tufted dandelions peeking out of the sidewalk cracks, the San Gabriel Mountains rising ten thousand feet above the valley, glowed pink, translucent in morning light. I saw the mountains for the first time at the age of eight soon after moving from Bisbee to Monrovia, California.

I stood neck crooked gazing at Mount Wilson, 5,000 feet high. “You can’t get lost in this valley,” Uncle Green said. “Just look toward the mountains, they’re always true north.” Since that day, I believed I could navigate life without a compass.

At the school entrance, orange remnants clung to the branches of a liquid amber sapling ravaged by last night’s storm. Beyond the tender tree, children dashed across the sunburnt grass, laughing. In Terry’s classroom, newsprint penned in fourth-grade cursive lined the corkboard. Mrs. Strong, well-coiffed and a bit older than me, sat at her desk against a wall of windows framing the mountains close enough to touch.

Making excuses for my husband’s absence, I squeezed into a child’s desk opposite the teacher waiting to be reprimanded for my failure as a parent.

Ditching school and smoking may be a sign of a deeper problem, she said. A cry for help. “Is Terry upset about something? Are there any problems at home?”

“No, everything’s fine.” Stuart’s nightly drunkenness was my problem, not Terry’s.

“In that case, perhaps a doctor could prescribe Ritalin, a drug to help him control his impulsive behavior, to help him focus.”

Granted, jumping off the roof with Alex last summer seemed a bit impulsive, but Terry was focused. I told her he played the accordion, pitched in Little League, was reading, The Secrets of Magic, and spent hours practicing sleight-of-hand, card, and coin tricks but I couldn’t tell her why drugs scared me, doctor prescribed or otherwise. God knows, I wanted to choose life for me and my children. Addicted to nicotine for eleven years, I’d tried to quit. I hated my mother’s smoking but rebelling against her, I started at eighteen and married another smoker three years later.

I’d also taken amphetamine-laced diet pills prescribed by our family doctor, on and off since seventh grade. My mother, a registered nurse, washed her own prescription down with Coke and Jack Daniels, and I secretly feared Terry’s biological father might not be Stuart but a friend’s brother, a one-night-stand drug addict just released from prison.

“My son’s only nine. I don’t want him taking drugs!”

Her voice softened. “I’m only asking you to consider it.” The kindness in Mrs. Strong’s muddied my mascara with tears.

“Thank you, I’ll think about what you said.” I walked home in the shadow of the true north mountain bleached colorless in midday sun.

I cleared my palette and paint rags off the kitchen table, peeled potatoes, and shoved a chicken in the oven to roast for an hour. Stuart expected dinner on the table at two in the afternoon, an hour before he left for work, and for me to cook like his Pennsylvania Dutch mother, a good cook also named Eva. “Beans are a side dish!” he scowled the first time I served pinto beans and cornbread for dinner, my Southern family favorite.

We both craved our childhood comfort foods, but I gave up mine. Instead of cooking black-eyed peas, pinto lima beans and ham hocks, I warmed up canned peas and creamed corn and cooked potatoes: mashed, baked, or hash browned. The daily menu included roast beef, chicken, or meatloaf—but always potatoes.

Stuart dragged himself out of bed shaved. Sitting at the head of the kitchen table scooping mashed potatoes on his fork, he asked what the teacher said.

“She said it’s serious.”

“A little father-son chat ought’ a straighten him out,” he said, pulling a cigarette from his shirt pocket.

After school, Stuart sat across the kitchen table from Terry. The sun beaming in the window bathed his freckled face in Rembrandt lighting like the Dutch master’s brooding portrait of Titus, the artist’s only child who survived beyond infancy.

“How’d it go?” I asked my husband before he left for work. He said he had everything under control, he’d grounded Terry from that troublemaker, Alex and added, “You know, boys will be boys!”

Did puberty blow in like a windstorm when least expected? My sweet boy seemed too young to relinquish childhood, but adolescence loomed on the horizon. I wanted my children to have role models. I considered Terry smoking at school, a wakeup call. Cornering Stuart in the hallway leaving for work, I told him we must stop smoking to set a better example.

“I’m not going to quit,” he said storming out. “Stop bugging me about it!” Leaning against the car in the driveway, looking like the Trickster, the sinister clown I’d painted in The Harlequins, he cupped his hands to protect the flame from the wind and lit a Camel.

What did he mean boys will be boys? Like his father, Stuart started smoking at thirteen. Did my husband consider our nine-year-old boy smoking and ditching school some sick sort of masculine bonding? Mrs. Strong suggested playing hooky and smoking signaled a deeper problem, confirming my fear that the sins of the fathers had passed to the next generation, our son, but I wanted to believe Stuart had everything under control and the crisis a normal rite of passage, “You know, boys will be boys,” like he said.

I stood in the doorway inhaling the minty aroma of the thirteen eucalyptus in our backyard. The towering tree’s long silvery leaves hung limp pointing toward the earth, denying the mayhem of last night’s storm.

n Grecian art, I decided to make homemade bread in my kitchen with plenty of light and free pesky snails. Wheat, the gift of Mother Earth would feed my family when the famine came.

On a cold winter morning, the kids at school, Stuart sleeping till noon, I found a Betty Crocker recipe for whole wheat bread. Preparing my palette, I spread the all-purpose, wholewheat flour, butter, brown sugar and salt on the table. The magic potion—baker’s dry yeast came with the label, WARNING: don’t kill the yeast!

Like the fragile seeds we planted, breadmaking required proper conditions for germination and growth. I mixed the flour and yeast and set it aside.

STIR: sugar, salt, and butter in a saucepan, heat to 120 degrees. CHECK: temperature with an instant-read-thermometer. If mixture is too hot the yeast will die. The bread won’t rise. BEAT: three minutes with electric mixer. I didn’t have a mixer or a thermometer, but neither did my ancestors who nourished their children with the bread of life. I mixed the dough with a wooden spoon for a long time.

KNEAD: six to eight minutes. Pounding the dough on the floured board released my pent-up resentment toward my husband’s bad jokes about my weight, coming home drunk, and smoking in the house after I’d begged not to. Angry, I pounced on the dough. I reread directions for kneading: Gently fold the dough, push down with the heel of your hand. Repeat until firm and elastic. I covered the over-kneaded dough with a dish cloth.

LET RISE: Ninety minutes later, the dough doubled in size and risen indeed. “Halleluiah!” I did not kill the yeast! Humming a hymn, I gently punched down the dough, divided in half and let it rest–again. Baking bread apparently required patience and periods of rest. Channeling Mother Earth, I patted and pinched the dough into two loaves. COVER and let rise again to almost double in size—about thirty minutes. “Good grief.” I spent the whole morning making two loaves of bread and they weren’t done yet! Then, I remembered the women who for hundreds of years, patiently waited for the dough to rest and rise again and again–one last time.

BAKE forty minutes. The aroma of homemade bread fed my soul. Breaking a piece off the warm loaf, I whispered, strength for the journey, not knowing the strength I needed or what lie ahead.

![]()

==========================

There is nothing to fear, the angel says.

Every word spoken and unspoken, every action taken and not taken occurred exactly as it should be and in perfect order. Love is all there is. It’s all so beautiful, complete with the music.

And this music will play until this story is told.

***